Day One Hundred: A Stream Through the Meadow by Arthur Parton

Hello and welcome to Day 100 of 100 days of Tonalism.

Today's study is 'A Stream Through the Meadow' by Arthur Parton.

Well, we've made it to the 100 and I'm proud to say without any gap or days missed. That wasn't always easy especially when I came down with a very nasty flu, however we made it!

Arthur Parton seems to be a popular 19th century painter, lesser known today. Born in 1842 and died in 1914, I've read some biographical information about him on today's video narration, so please check that out.

Just reading over some of my initial blog posts at the start of this series of 100 days of Tonalism; I set out to do four basic things:

I feel that I more than accomplished those aims and I'm very happy with the studies I've painted and satisfied with the writing on the blog and my video work. I would've liked to have been more authoritative in my knowledge of art history and I would've liked to have spent more time with the video narration and the writing that I've done.

However, I've done this blog and the attendant studies and videos in the same spirit that I produce all of my work, and that is through intellectual intention combined with intuition and perspiration. The creative process is intriguing to study in and of itself, and though I ponder it, I do not spend too much time engaged in that endeavor. I prefer to spend my time creating paintings, and I am happy to say that I do that every day and have through the writing of every post on this blog.

It would be disingenuous to say that this project has not affected the quantity of my own paintings that I could've accomplished. It has had a strong positive impact on my work though, and for that I am grateful. As I've stated on this blog previously, I am predominantly self educated having never attended art school or university.

This is one of the main reasons I decided to interrupt the usual work flow of my painting with a period of study and education. I've also succeeded in creating some beautiful studies, and hopefully the work I've done here will help to educate and inspire other artists,laypersons and art collectors to more fully understand and appreciate this compelling period in art history, as well as my contemporary take on Tonalism.

As I stated on today's video narration, I will be continuing this blog on a weekly basis. It occurred to me today that were I to consistently do this I would have another 56 blog posts in a year from now, with far less strain. I intend to put up some videos of my own Tonalist painting and I will be writing accompanying posts. We will probably get a lot deeper into some of the topics and issues that I've discussed on this blog so far, but with a bit more of a personal slant.

Thanks for staying with me this far and please tune in next week to see what I've hatched..

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about a 'Stream through the Meadow' by Arthur Parton; it occurs to me now that I might have selected perhaps an Inness or a Murphy, to end the series but they've had their day and this is Arthur's chance to shine.

I wasn't able to discover a whole lot of biographical information about Arthur online but what I did find I read in today's video. And I did notice that he was referred to as an Impressionist, however the study that we're doing after his painting today is clearly a Tonalist effort on his part.

This painting of his was selected because it is the type of composition that I enjoy painting in my own work. I like to paint a road, river or path that leads the viewer up into the painting and masses of trees on either side with a large expansive sky.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

Today's study is 'A Stream Through the Meadow' by Arthur Parton.

|

| Painted after - A Stream Through the Meadow by Arthur Parton, Study by M Francis McCarthy - Size 5x7, Oil on wood panel |

Well, we've made it to the 100 and I'm proud to say without any gap or days missed. That wasn't always easy especially when I came down with a very nasty flu, however we made it!

Arthur Parton seems to be a popular 19th century painter, lesser known today. Born in 1842 and died in 1914, I've read some biographical information about him on today's video narration, so please check that out.

Just reading over some of my initial blog posts at the start of this series of 100 days of Tonalism; I set out to do four basic things:

- Increase awareness of this vital and fascinating movement in painting.

- Help to expand the audience for my work.

- Expand the general public's awareness and appreciation of Tonalism.

- Generate income from the sale of these fine arts studies.

I feel that I more than accomplished those aims and I'm very happy with the studies I've painted and satisfied with the writing on the blog and my video work. I would've liked to have been more authoritative in my knowledge of art history and I would've liked to have spent more time with the video narration and the writing that I've done.

However, I've done this blog and the attendant studies and videos in the same spirit that I produce all of my work, and that is through intellectual intention combined with intuition and perspiration. The creative process is intriguing to study in and of itself, and though I ponder it, I do not spend too much time engaged in that endeavor. I prefer to spend my time creating paintings, and I am happy to say that I do that every day and have through the writing of every post on this blog.

It would be disingenuous to say that this project has not affected the quantity of my own paintings that I could've accomplished. It has had a strong positive impact on my work though, and for that I am grateful. As I've stated on this blog previously, I am predominantly self educated having never attended art school or university.

This is one of the main reasons I decided to interrupt the usual work flow of my painting with a period of study and education. I've also succeeded in creating some beautiful studies, and hopefully the work I've done here will help to educate and inspire other artists,laypersons and art collectors to more fully understand and appreciate this compelling period in art history, as well as my contemporary take on Tonalism.

As I stated on today's video narration, I will be continuing this blog on a weekly basis. It occurred to me today that were I to consistently do this I would have another 56 blog posts in a year from now, with far less strain. I intend to put up some videos of my own Tonalist painting and I will be writing accompanying posts. We will probably get a lot deeper into some of the topics and issues that I've discussed on this blog so far, but with a bit more of a personal slant.

Thanks for staying with me this far and please tune in next week to see what I've hatched..

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about a 'Stream through the Meadow' by Arthur Parton; it occurs to me now that I might have selected perhaps an Inness or a Murphy, to end the series but they've had their day and this is Arthur's chance to shine.

I wasn't able to discover a whole lot of biographical information about Arthur online but what I did find I read in today's video. And I did notice that he was referred to as an Impressionist, however the study that we're doing after his painting today is clearly a Tonalist effort on his part.

This painting of his was selected because it is the type of composition that I enjoy painting in my own work. I like to paint a road, river or path that leads the viewer up into the painting and masses of trees on either side with a large expansive sky.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Original painting, A Stream Through the Meadow by Arthur Parton |

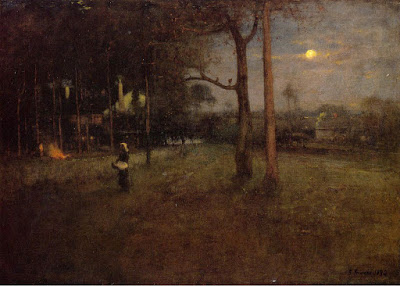

Day Ninety Nine: October by George Inness

Hello and welcome to Day 99 of 100 days of Tonalism.

Today's study is 'October' by George Inness.

One more day to go and this is our last Inness. I knew I would enjoy making studies after Inness' paintings and I'm so glad that I've had the experience, though it was a lot of hard work. I will be reading from the book George Inness by Nicolai Cikovsky in today's video narration, so please check that out.

Well, we spent the last couple days talking about Modern art which might seem a little disingenuous as the name of the blog is Tonalist Paintings by M Francis McCarthy, and the series we are in is called 100 days of Tonalism.

The reasons I brought up Modern art here are because it has nearly the full attention and financial backing of the current art establishment. Representational art has been making some major inroads though and after 100 years of disparaging representational art, many artists are tired of the freak show and are looking for meaning beyond clever artspeak.

Today, since we have just one more post to go, I think I'll just talk about what attracted me to Tonalism and why I love it. I've always enjoyed art and when I was a young man I was captivated by the art of men like Frank Frazetta and all of the comic greats from my era. I had awareness of fine art as well and a deep respect for people like Michelangelo and Albrecht Durer. As I stated in a previous blog post it wasn't until sometime in the 80s that I began to visualize wanting to be a landscape painter. I've outlined most of that process of discovery fairly well elsewhere in this series of blog posts, so have a look for that if you are interested.

The major thing that has attracted me to Tonalist painting is the richness and strong emotive qualities of it. There are many ways to paint a landscape but after my initial exposure to Tonalism I felt I'd discovered the pinnacle of what had been accomplished by the great artists of the late 1800s and early 20th century. Sadly, as some of you know, much of this work was forgotten as were the artists that created it. This is changing and I'd like to think that my series here, 100 days of Tonalism is helping in that regard.

I was talking to a friend of mine the other day about a book called the Agony and the Ecstasy about Michelangelo. I read this book when I was a young man and it had a great impact on me. The main thing that struck me about Michelangelo was how passionate he was. At that time in Europe, art was primarily two-dimensional/flat in feel, and though there were plenty of representations of people, often times you could not clearly make out any real anatomy for all of the rendering of folds that was going on. The Europeans did have access to ancient statuary created by the Romans and the Greeks that depicted the human figure correctly and powerfully, but there was little understanding about anatomy in the pre renaissance or, how to accurately render it.

Because Michelangelo was aware of this huge disparity between, what had been in the past and how it surpassed art in his time, he was curious about how to create anatomical art himself that would match or, even surpass the achievements of the Greeks and Romans. He set about teaching himself anatomy studiously even to the point where he would dissect corpses (an act that was illegal in his day).

The reason I bring up Michelangelo in regards to Tonalism is that I see the same sort of thing happening now with landscape painting, in that there are all these masterful Tonalist paintings that exist however, because they've been mostly bypassed and forgotten by art history, many artists are unaware of the achievement and just sort of do whatever it is they're doing, whether that is working in some sort of Impressionist vein, or just doing their best to copy photographs using oil paint. Like Michelangelo I can see that much of the landscape painting that is done by contemporary artists falls far short of the high mark set by the Tonalists at the peak of landscape painting.

After becoming aware of Tonalism I set about doing my best to create paintings that captured the same sort of mood and spiritual depth as the Masters. Whether I've succeeded or not is perhaps best judged by others but I am certainly proud of the attempt and I will continue to create landscape paintings that I find personally moving until I am no longer able to.

As I stated above there are many ways that you can accomplish landscape painting and many moods and ideas can be conveyed by various approaches. For me, no other school of painting has come even close to the level of Tonalism and that is why I spent the better part of this year working on this series in an endeavor to learn more, and also to bring greater awareness to this awesome school of art.

If you are a person that has any questions about Tonalism or Tonalist painting that you feel I can answer, I can be reached easily through my website Landscaperpainter.co.nz I am happy to help you in any way I can, so do not hesitate to contact me.

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about 'October' by George Inness; this is a really great painting by George and one of the studies I am most proud of doing.

I'm very happy with the textural approach that I achieved on the study and as I've stated in previous blog posts, this has very much informed my own Tonalist painting.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Painted after - October by George Inness, Study by M Francis McCarthy - Size 5x7, Oil on wood panel |

One more day to go and this is our last Inness. I knew I would enjoy making studies after Inness' paintings and I'm so glad that I've had the experience, though it was a lot of hard work. I will be reading from the book George Inness by Nicolai Cikovsky in today's video narration, so please check that out.

Well, we spent the last couple days talking about Modern art which might seem a little disingenuous as the name of the blog is Tonalist Paintings by M Francis McCarthy, and the series we are in is called 100 days of Tonalism.

The reasons I brought up Modern art here are because it has nearly the full attention and financial backing of the current art establishment. Representational art has been making some major inroads though and after 100 years of disparaging representational art, many artists are tired of the freak show and are looking for meaning beyond clever artspeak.

Today, since we have just one more post to go, I think I'll just talk about what attracted me to Tonalism and why I love it. I've always enjoyed art and when I was a young man I was captivated by the art of men like Frank Frazetta and all of the comic greats from my era. I had awareness of fine art as well and a deep respect for people like Michelangelo and Albrecht Durer. As I stated in a previous blog post it wasn't until sometime in the 80s that I began to visualize wanting to be a landscape painter. I've outlined most of that process of discovery fairly well elsewhere in this series of blog posts, so have a look for that if you are interested.

The major thing that has attracted me to Tonalist painting is the richness and strong emotive qualities of it. There are many ways to paint a landscape but after my initial exposure to Tonalism I felt I'd discovered the pinnacle of what had been accomplished by the great artists of the late 1800s and early 20th century. Sadly, as some of you know, much of this work was forgotten as were the artists that created it. This is changing and I'd like to think that my series here, 100 days of Tonalism is helping in that regard.

I was talking to a friend of mine the other day about a book called the Agony and the Ecstasy about Michelangelo. I read this book when I was a young man and it had a great impact on me. The main thing that struck me about Michelangelo was how passionate he was. At that time in Europe, art was primarily two-dimensional/flat in feel, and though there were plenty of representations of people, often times you could not clearly make out any real anatomy for all of the rendering of folds that was going on. The Europeans did have access to ancient statuary created by the Romans and the Greeks that depicted the human figure correctly and powerfully, but there was little understanding about anatomy in the pre renaissance or, how to accurately render it.

Because Michelangelo was aware of this huge disparity between, what had been in the past and how it surpassed art in his time, he was curious about how to create anatomical art himself that would match or, even surpass the achievements of the Greeks and Romans. He set about teaching himself anatomy studiously even to the point where he would dissect corpses (an act that was illegal in his day).

The reason I bring up Michelangelo in regards to Tonalism is that I see the same sort of thing happening now with landscape painting, in that there are all these masterful Tonalist paintings that exist however, because they've been mostly bypassed and forgotten by art history, many artists are unaware of the achievement and just sort of do whatever it is they're doing, whether that is working in some sort of Impressionist vein, or just doing their best to copy photographs using oil paint. Like Michelangelo I can see that much of the landscape painting that is done by contemporary artists falls far short of the high mark set by the Tonalists at the peak of landscape painting.

After becoming aware of Tonalism I set about doing my best to create paintings that captured the same sort of mood and spiritual depth as the Masters. Whether I've succeeded or not is perhaps best judged by others but I am certainly proud of the attempt and I will continue to create landscape paintings that I find personally moving until I am no longer able to.

As I stated above there are many ways that you can accomplish landscape painting and many moods and ideas can be conveyed by various approaches. For me, no other school of painting has come even close to the level of Tonalism and that is why I spent the better part of this year working on this series in an endeavor to learn more, and also to bring greater awareness to this awesome school of art.

If you are a person that has any questions about Tonalism or Tonalist painting that you feel I can answer, I can be reached easily through my website Landscaperpainter.co.nz I am happy to help you in any way I can, so do not hesitate to contact me.

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about 'October' by George Inness; this is a really great painting by George and one of the studies I am most proud of doing.

I'm very happy with the textural approach that I achieved on the study and as I've stated in previous blog posts, this has very much informed my own Tonalist painting.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Original painting, October by George Inness |

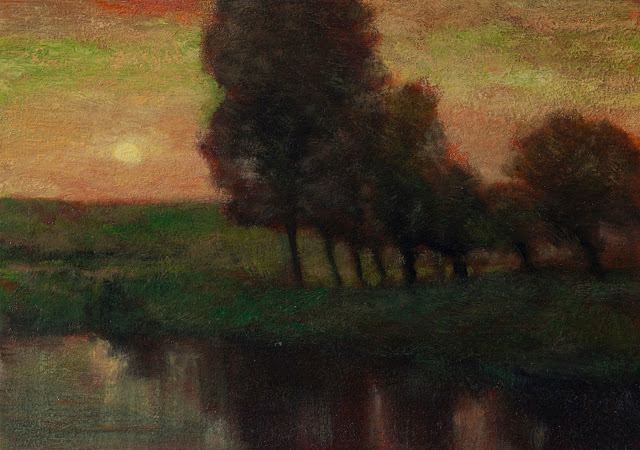

Day Ninety Eight: Sunset by Charles Warren Eaton

Hello and welcome to day 98 of 100 days of Tonalism.

Today's study is 'Sunset' by Charles Warren Eaton.

We've done a lot of Eaton's in the series and this is the last one. As I mentioned in our previous Eaton post I recently received a book by David A Cleveland called Intimate Landscapes Charles Warren Eaton and the Tonalist movement in American art 1880 to 1920. This book was written before Davids seminal work A History of American Tonalism 1880 to 1920 and is currently out of print. The book was not cheap and I recommend it only for only the most fanatical fans of Tonalism out there (which would include myself). I will be reading from this book today in the video narration so please check that out.

Yesterday I was writing about how there is nothing new in art. I'm afraid my post devolved into yet another rant against a Modern art. I'd like to qualify my views on Modern art a little more extensively today, as this is a topic with a lot of grays and my post yesterday made it seem like my views are black and white.

I am not arguing (as some do) that there should never have been a shift in painting towards, what is now termed Modern art. The reality is that there are many Modern artists whose work I admire and find moving. A short list off the top of my head would include Rothko, Gerhard Richter, Franz Klein, Picasso, Gauguin, late period Willem de Kooning and others that I'm sure just are not coming to mind at the moment. I'm also fan of much of the surrealist work done by Salvador Dali.

I am not an art historian, I am an artist. For that reason I feel absolutely no need to be objective about Modern art or the reasons why it came into existence. I do think that it was probably a good thing that Modern art came along to shake things up. Although, truth be told, things were changing prior to abstracted work taking over, starting with the Barbizon School, moving to Impressionism and post-impressionism and of course Tonalism. Prior to Modern art, some of the classic representational art was becoming staid, over polished and plastic in quality. It's clear that something needed to change.

Even though art needed to shift, much of value was lost in the process, to the point where we're facing an extreme devolution of art now that needs to be remedied. I don't want to list the names of offending Modern artists but I will say that a majority of modern art that I am exposed to, I find to be loathsome and highly offensive. The story that always comes to mind is the Emperor's new clothes. As in that story, something that did not exist and was not worth admiring was regarded highly and lies were put forward as truth while everyone clapped along.

I will always find this offensive. I do not blame artists that are enmeshed in the Modern art hyperbole. Well, I don't blame them much. The fact that some non-representational modern art is actually moving and worth looking at just complicates matters.

In most things, I think you can apply the 80/20 rule but when it comes to much of contemporary modern art, I think it's probably more accurate to apply the 98% versus 2% rule. In other words, 98% of contemporary modern art is dreck and does not deserve to exist, much less be promulgated as anything worth paying attention to let alone paid for.

Sorry, (ahem) it's so easy for me to rant about this topic because I feel very strongly about it. I do try to be fair though, and since that was the initial purpose of this blog post, let me just end todays post here by saying that some Modern art is absolutely wonderful and some Modern artists are really fantastic. Although I often tar the entire movement of contemporary Modern art with the same brush, it deserves to be stated that some of this stuff is okay and a very small percentage is better than okay, it's great.

It's up to each of us as artists or appreciators of art, in the contemporary milieu, to set upon a course whereby we are separating the wheat from the chaff of Modern art, at least for ourselves.

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about 'Sunset' by Charles Warren Eaton; this is a later period Eaton and I've seen it online quite a few times. In the painting by Eaton you can make out that the background has houses in it. I didn't bother to put that in preferring to keep it somewhat oblique. I enjoyed painting this study and I like the way that the gold and ochre tones contrasts against the green in the foreground.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Painted after - Sunset by Charles Warren Eaton, Study by M Francis McCarthy - Size 5x7, Oil on wood panel |

We've done a lot of Eaton's in the series and this is the last one. As I mentioned in our previous Eaton post I recently received a book by David A Cleveland called Intimate Landscapes Charles Warren Eaton and the Tonalist movement in American art 1880 to 1920. This book was written before Davids seminal work A History of American Tonalism 1880 to 1920 and is currently out of print. The book was not cheap and I recommend it only for only the most fanatical fans of Tonalism out there (which would include myself). I will be reading from this book today in the video narration so please check that out.

Yesterday I was writing about how there is nothing new in art. I'm afraid my post devolved into yet another rant against a Modern art. I'd like to qualify my views on Modern art a little more extensively today, as this is a topic with a lot of grays and my post yesterday made it seem like my views are black and white.

I am not arguing (as some do) that there should never have been a shift in painting towards, what is now termed Modern art. The reality is that there are many Modern artists whose work I admire and find moving. A short list off the top of my head would include Rothko, Gerhard Richter, Franz Klein, Picasso, Gauguin, late period Willem de Kooning and others that I'm sure just are not coming to mind at the moment. I'm also fan of much of the surrealist work done by Salvador Dali.

I am not an art historian, I am an artist. For that reason I feel absolutely no need to be objective about Modern art or the reasons why it came into existence. I do think that it was probably a good thing that Modern art came along to shake things up. Although, truth be told, things were changing prior to abstracted work taking over, starting with the Barbizon School, moving to Impressionism and post-impressionism and of course Tonalism. Prior to Modern art, some of the classic representational art was becoming staid, over polished and plastic in quality. It's clear that something needed to change.

Even though art needed to shift, much of value was lost in the process, to the point where we're facing an extreme devolution of art now that needs to be remedied. I don't want to list the names of offending Modern artists but I will say that a majority of modern art that I am exposed to, I find to be loathsome and highly offensive. The story that always comes to mind is the Emperor's new clothes. As in that story, something that did not exist and was not worth admiring was regarded highly and lies were put forward as truth while everyone clapped along.

I will always find this offensive. I do not blame artists that are enmeshed in the Modern art hyperbole. Well, I don't blame them much. The fact that some non-representational modern art is actually moving and worth looking at just complicates matters.

In most things, I think you can apply the 80/20 rule but when it comes to much of contemporary modern art, I think it's probably more accurate to apply the 98% versus 2% rule. In other words, 98% of contemporary modern art is dreck and does not deserve to exist, much less be promulgated as anything worth paying attention to let alone paid for.

Sorry, (ahem) it's so easy for me to rant about this topic because I feel very strongly about it. I do try to be fair though, and since that was the initial purpose of this blog post, let me just end todays post here by saying that some Modern art is absolutely wonderful and some Modern artists are really fantastic. Although I often tar the entire movement of contemporary Modern art with the same brush, it deserves to be stated that some of this stuff is okay and a very small percentage is better than okay, it's great.

It's up to each of us as artists or appreciators of art, in the contemporary milieu, to set upon a course whereby we are separating the wheat from the chaff of Modern art, at least for ourselves.

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about 'Sunset' by Charles Warren Eaton; this is a later period Eaton and I've seen it online quite a few times. In the painting by Eaton you can make out that the background has houses in it. I didn't bother to put that in preferring to keep it somewhat oblique. I enjoyed painting this study and I like the way that the gold and ochre tones contrasts against the green in the foreground.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Original painting,Sunset by Charles Warren Eaton |

Day Ninety Seven: Le Monastere Derrier Les-Arbres by Camille Corot

Hello and welcome to day 97 of 100 days of Tonalism.

Today's study is 'Le Monastere Derrier Les-Arbres' by Camille Corot.

Camile Corot was very influential on the Tonalist movement in American art. Camille was not actually a Tonalist painter himself, he was a member of the French Barbizon school. Today's video features a track from my album It Never Was, so please check that out.

I'd like to talk today about the concept of newness and modern art. Frankly, there is no such thing as newness in art. What passes for newness these days? Is it art that has been done over and over again for the last hundred years? The idea that the purpose of art is to shock, comment on societal ills or serve the whims of fashion is not new in any way, shape or form. Yet, these ideas are still passed off over and over again as fresh.

There is a conspiracy promulgated by art schools and the fine art establishment in general to keep artists from researching the true history of art, and also from developing a real skillset based on hours of experience drawing and painting. What is replacing this valid education based on experience, is some sort of idea that art should strike you like a lightning bolt out of the blue, that the less you know about (real) art the better you will be.

When people do not have a skill set based on actual experience most of their artistic output will be regurgitated from the work of others and not in a good way. What I mean is a lot of cribbing/stealing decorated with elusive,enigmatic titles and disguised as original work.

If the purpose of your work is to be clever and to receive accolades from the art establishment all you really need to do is learn how to do artspeak and kiss the asses of the local art establishment. I've talked about this negative idea called Modern art many times. I would apologize except for the fact that so many regular people have given up on fine art and just dismissed it (often deservedly) as vacant and lacking in true purpose or meaning.

When you see a painting of some colored dots assembled in rows above each other selling for 40 or $50,000 (that was not even painted by the artist whose name is going on the canvas), most normal people will disregard this as bogus and simply spend their time and attention in more fruitful pursuits, like sports, eating stuff or watching Netflix.

What's unfortunate about this state of affairs, is that fine art has the power and ability to spiritually uplift humanity and yet many worthy artists receive little support financially or emotionally from their communities. Perhaps the reason for this is that many of our museums are mostly full of claptrap instead of art of a moving and significant nature.

Getting back to our theme today. There is nothing new that has not already been done. Nothing. So what is a contemporary artist to do?

I believe that this question is best answered with self-examination and consideration of what has come before. When a cabinet maker creates a piece of furniture, he does not set out to create something new, he sets out to build something that is functional, useful and beautiful. I believe you can apply this same sort of criteria to the creation of fine art.

If your intention is to uplift people's spirits and create beauty, you need to acquire the skills that will make this possible. You should study the work of the past Masters to accomplish this goal. By doing this and being true to who and what you are as a human being and an artist, your work will be fresh and new, There can only be one of each of us, but to create great work, that uniqueness must be educated, tested, toughened and most of all experienced.

I'm not saying that you should actively copy the work of past Masters unless you are doing so (as I am in this series) for the sake of education or illumination. I believe you should create from the heart and from the deepest recesses of your own being. And there is absolutely no problem with that creation being informed by the great work that has come before.

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about 'Le Monastere Derrier Les-Arbres' by Camille Corot; this was an interesting study to do/ One of the best parts of Camille's painting is the atmospheric quality. I did my best to get this across in my study as well as the muted taupe and silver quality of his painting.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Painted after - Le Monastere by Camille Corot, Study by M Francis McCarthy - Size 5x7, Oil on wood panel |

Camile Corot was very influential on the Tonalist movement in American art. Camille was not actually a Tonalist painter himself, he was a member of the French Barbizon school. Today's video features a track from my album It Never Was, so please check that out.

I'd like to talk today about the concept of newness and modern art. Frankly, there is no such thing as newness in art. What passes for newness these days? Is it art that has been done over and over again for the last hundred years? The idea that the purpose of art is to shock, comment on societal ills or serve the whims of fashion is not new in any way, shape or form. Yet, these ideas are still passed off over and over again as fresh.

There is a conspiracy promulgated by art schools and the fine art establishment in general to keep artists from researching the true history of art, and also from developing a real skillset based on hours of experience drawing and painting. What is replacing this valid education based on experience, is some sort of idea that art should strike you like a lightning bolt out of the blue, that the less you know about (real) art the better you will be.

When people do not have a skill set based on actual experience most of their artistic output will be regurgitated from the work of others and not in a good way. What I mean is a lot of cribbing/stealing decorated with elusive,enigmatic titles and disguised as original work.

If the purpose of your work is to be clever and to receive accolades from the art establishment all you really need to do is learn how to do artspeak and kiss the asses of the local art establishment. I've talked about this negative idea called Modern art many times. I would apologize except for the fact that so many regular people have given up on fine art and just dismissed it (often deservedly) as vacant and lacking in true purpose or meaning.

When you see a painting of some colored dots assembled in rows above each other selling for 40 or $50,000 (that was not even painted by the artist whose name is going on the canvas), most normal people will disregard this as bogus and simply spend their time and attention in more fruitful pursuits, like sports, eating stuff or watching Netflix.

What's unfortunate about this state of affairs, is that fine art has the power and ability to spiritually uplift humanity and yet many worthy artists receive little support financially or emotionally from their communities. Perhaps the reason for this is that many of our museums are mostly full of claptrap instead of art of a moving and significant nature.

Getting back to our theme today. There is nothing new that has not already been done. Nothing. So what is a contemporary artist to do?

I believe that this question is best answered with self-examination and consideration of what has come before. When a cabinet maker creates a piece of furniture, he does not set out to create something new, he sets out to build something that is functional, useful and beautiful. I believe you can apply this same sort of criteria to the creation of fine art.

If your intention is to uplift people's spirits and create beauty, you need to acquire the skills that will make this possible. You should study the work of the past Masters to accomplish this goal. By doing this and being true to who and what you are as a human being and an artist, your work will be fresh and new, There can only be one of each of us, but to create great work, that uniqueness must be educated, tested, toughened and most of all experienced.

I'm not saying that you should actively copy the work of past Masters unless you are doing so (as I am in this series) for the sake of education or illumination. I believe you should create from the heart and from the deepest recesses of your own being. And there is absolutely no problem with that creation being informed by the great work that has come before.

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about 'Le Monastere Derrier Les-Arbres' by Camille Corot; this was an interesting study to do/ One of the best parts of Camille's painting is the atmospheric quality. I did my best to get this across in my study as well as the muted taupe and silver quality of his painting.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Original painting, Le Monastere Derrier Les-Arbres by Camille Corot |

Day Ninety Six: Untitled by Robertson Kirtland Mygatt

Hello and welcome to day 96 of 100 days of Tonalism.

Today study is 'Untitled' by Robertson Kirtland Mygatt.

Robertson Kirtland Mygatt is a lesser-known Tonalist artist. I have found some biographical information about him which I've read in today's video narration, so please check that out.

Every artist is different and is motivated by different aspects of life to create art. For my part, I essentially decided to be an artist when I was about 13 years old. Art was just one of the many things that I was good at back then. Being a teenager, I was aware that it wouldn't be that long before I would have to leave the shelter of my family and make my own way in the world.

Though my personality was still forming in many ways, I had a decent amount of self-awareness, and after considering the types of career that would be complementary with my personality, I decided art would be the way to go.

From that time forward, I started applying myself industriously to learning how to draw. I remember doing an oil painting back then. I had such a clear image in my mind of what I wanted to do, yet when it came time to paint it, I discovered how little I knew about painting and, how difficult it would be to create something that was even close to comparable with the work of the artists that I admired.

I bailed on that early painting but I stuck with drawing. I would draw everyday, back then, I was very into comic books and I would spend time copying the pictures. I would draw the anatomy of the figures in the various panels. It wasn't long before I became aware of the differences between pencilers and inkers. I noticed that mediocre pencils could be made to look quite good if the penciler had a good inker and conversely that a great pencilled work could be super diminished with shoddy or haphazard inking.

I started teaching myself how to ink using dip pens, I also would use technical pens. After a while I learned how to use a sable brush to ink my pencil drawings. This put me quite far ahead of my peers that were also interested in drawing. They would work very hard on their pencil drawings but would be loath to ink them as they had no real experience of inking. I think that this early exposure to working with brushes and ink was very helpful for my later career as a oil painter.

The thing about ink is that it is much different than pencil. When you make a mark with pen and ink it is either black or white. There is no gray, no intermediate values just on or off. this approach to values provided good learning experience.

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about 'Untitled' by Robertson Kirtland Mygatt; Robert is one of those artists that you really need to know his middle name to find out anything about. He seems to been almost completely forgotten. This painting is very representative of the work of his I've seen in my research into him online.

I've actually completed two studies, having sold the first version a few months ago. It's interesting to me how my painting changes with time and accompanying shifts in consciousness.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Painted after - Untitled by Robertson Kirtland Mygatt, Study by M Francis McCarthy - Size 5x5, Oil on wood panel |

Robertson Kirtland Mygatt is a lesser-known Tonalist artist. I have found some biographical information about him which I've read in today's video narration, so please check that out.

Every artist is different and is motivated by different aspects of life to create art. For my part, I essentially decided to be an artist when I was about 13 years old. Art was just one of the many things that I was good at back then. Being a teenager, I was aware that it wouldn't be that long before I would have to leave the shelter of my family and make my own way in the world.

Though my personality was still forming in many ways, I had a decent amount of self-awareness, and after considering the types of career that would be complementary with my personality, I decided art would be the way to go.

From that time forward, I started applying myself industriously to learning how to draw. I remember doing an oil painting back then. I had such a clear image in my mind of what I wanted to do, yet when it came time to paint it, I discovered how little I knew about painting and, how difficult it would be to create something that was even close to comparable with the work of the artists that I admired.

I bailed on that early painting but I stuck with drawing. I would draw everyday, back then, I was very into comic books and I would spend time copying the pictures. I would draw the anatomy of the figures in the various panels. It wasn't long before I became aware of the differences between pencilers and inkers. I noticed that mediocre pencils could be made to look quite good if the penciler had a good inker and conversely that a great pencilled work could be super diminished with shoddy or haphazard inking.

I started teaching myself how to ink using dip pens, I also would use technical pens. After a while I learned how to use a sable brush to ink my pencil drawings. This put me quite far ahead of my peers that were also interested in drawing. They would work very hard on their pencil drawings but would be loath to ink them as they had no real experience of inking. I think that this early exposure to working with brushes and ink was very helpful for my later career as a oil painter.

The thing about ink is that it is much different than pencil. When you make a mark with pen and ink it is either black or white. There is no gray, no intermediate values just on or off. this approach to values provided good learning experience.

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about 'Untitled' by Robertson Kirtland Mygatt; Robert is one of those artists that you really need to know his middle name to find out anything about. He seems to been almost completely forgotten. This painting is very representative of the work of his I've seen in my research into him online.

I've actually completed two studies, having sold the first version a few months ago. It's interesting to me how my painting changes with time and accompanying shifts in consciousness.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Original painting, Untitled by Robertson Kirtland Mygatt |

Day Ninety Five: By the Lake by George Inness

Hello and welcome day 95 to 100 days of Tonalism.

Today's study is 'By the Lake' by George Inness.

Just one more George Inness study after this one. This piece I believe is mid period Inness, most likely painted somewhere in the 1870s. On today's video narration, I read some biographical information about George Inness from the book George Inness by Nicolai Cikovsky Jr so please check that out.

I was reading from a book I just acquired about Charles Warren Eaton today. I mentioned this book in our last post about Charles Warren Eaton. The book was very interesting because it was discussing the beginnings of the Tonalist movement in art.

In many ways this period in art history from 1880 to 1920 is disregarded by some art historians or it is lumped in with the Barbizon school. In actuality, Tonalism is a very American form of painting and is quite different from Barbizon work. Although many of the greatest proponents of Tonalism were trained in the Barbizon school, what they created in the United States was very much a reflection of American and not European art.

Previous to the Tonalist movement, the style of painting that was popular in the United States was a movement called the Hudson River School. I've mentioned them many times on this blog. The Hudson River School was dedicated to capturing the splendor of the American landscape in large canvases, exquisitely detailed and rendered with polished finishes. In many ways this movement in art was running along with Tonalism which superseded and improved upon it.

Whereas the Hudson River School was about objective depictions of the vastness of nature with scenes often depicting glorious vistas of the unexplored American wilderness, Tonalism endeavored to portray a more subjective and emotional approach. Many Tonalist paintings being of every day farm life, of vacant fields or views by a river or creek. This Tonalist move from the objective to subjective is one of the precursors to modern art.

Though Tonalism is considered to be representational art; because it features the subjective, it is more poetical than scientific and, for that reason, timeless. When I first came upon this type of work I could not believe that it was not more widely known about. Our blog post yesterday spoke about some of the ways and reasons that artwork from the representational era is considered by some to be passé and not relevant to modern sensibilities.

If this sort of thinking was actually true, then there would be no reason to read any book that was published further back than 10 or 20 years. Anybody with any sense knows that this would be a stupid idea. So much classic literature going back to the Iliad by Homer is worthy of study and conveys emotion and poetry as powerfully now as it did when it was written.

This is true of fine painting as well. I dedicated a large portion of my working life this year to the study and promotion of these Tonalist Masters. I also devoted quite a lot of time to videotaping, editing videos and writing this blog. It's my way of learning on the job but also giving something back to the artists that came before me.

As someone who did not officially go to art school or study for any great length of time in the studio of a Master painter I felt it was incumbent upon me to take some time from my own painting life to learn more about how these great painters of the past accomplished the magnificent work that they did, and to share that knowledge and hopefully convert some of it to wisdom.

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about 'By the Lake' by George Inness; this was a fun and relatively easy study to do. As I stated in the video I enjoyed painting the sky and I really feel that it is the focal point of this painting.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Painted after - By the Lake by George Inness, Study by M Francis McCarthy - Size 5x7, Oil on wood panel |

Just one more George Inness study after this one. This piece I believe is mid period Inness, most likely painted somewhere in the 1870s. On today's video narration, I read some biographical information about George Inness from the book George Inness by Nicolai Cikovsky Jr so please check that out.

I was reading from a book I just acquired about Charles Warren Eaton today. I mentioned this book in our last post about Charles Warren Eaton. The book was very interesting because it was discussing the beginnings of the Tonalist movement in art.

In many ways this period in art history from 1880 to 1920 is disregarded by some art historians or it is lumped in with the Barbizon school. In actuality, Tonalism is a very American form of painting and is quite different from Barbizon work. Although many of the greatest proponents of Tonalism were trained in the Barbizon school, what they created in the United States was very much a reflection of American and not European art.

Previous to the Tonalist movement, the style of painting that was popular in the United States was a movement called the Hudson River School. I've mentioned them many times on this blog. The Hudson River School was dedicated to capturing the splendor of the American landscape in large canvases, exquisitely detailed and rendered with polished finishes. In many ways this movement in art was running along with Tonalism which superseded and improved upon it.

Whereas the Hudson River School was about objective depictions of the vastness of nature with scenes often depicting glorious vistas of the unexplored American wilderness, Tonalism endeavored to portray a more subjective and emotional approach. Many Tonalist paintings being of every day farm life, of vacant fields or views by a river or creek. This Tonalist move from the objective to subjective is one of the precursors to modern art.

Though Tonalism is considered to be representational art; because it features the subjective, it is more poetical than scientific and, for that reason, timeless. When I first came upon this type of work I could not believe that it was not more widely known about. Our blog post yesterday spoke about some of the ways and reasons that artwork from the representational era is considered by some to be passé and not relevant to modern sensibilities.

If this sort of thinking was actually true, then there would be no reason to read any book that was published further back than 10 or 20 years. Anybody with any sense knows that this would be a stupid idea. So much classic literature going back to the Iliad by Homer is worthy of study and conveys emotion and poetry as powerfully now as it did when it was written.

This is true of fine painting as well. I dedicated a large portion of my working life this year to the study and promotion of these Tonalist Masters. I also devoted quite a lot of time to videotaping, editing videos and writing this blog. It's my way of learning on the job but also giving something back to the artists that came before me.

As someone who did not officially go to art school or study for any great length of time in the studio of a Master painter I felt it was incumbent upon me to take some time from my own painting life to learn more about how these great painters of the past accomplished the magnificent work that they did, and to share that knowledge and hopefully convert some of it to wisdom.

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about 'By the Lake' by George Inness; this was a fun and relatively easy study to do. As I stated in the video I enjoyed painting the sky and I really feel that it is the focal point of this painting.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Original painting, By the Lake by George Inness |

Day Ninety Four: Hillside by John Francis Murphy

Hello welcome to Day 94 of 100 days of Tonalism.

Today's study is 'Hillside' by John Francis Murphy.

This is our last John Francis Murphy today, I saved one of the nicest studies for last. In today's video narration I read from the book A History of American Tonalism 1882-1920 by David A Cleveland, so please check that out.

Yesterday I was reading a very interesting post from a site called artrenewal.org. Artrenewal.org is a site that supports representational art and features the work of many artists throughout history as well as artists, it refers to as Living Masters. They run yearly competitions where they give prizes and they also have a large amount of imagery there. That is always been my predominant attraction to the site.

The article I was reading yesterday was very interesting. It was by a gentleman named Frederick Ross and the title of the article is 'Why Realism?'

I'm providing you with a link to the article here. It is very long and I cannot say that I agree with everything that Frederick says in it, however he makes some excellent points in regards to modern art. Those of you that have read this blog for any length of time will be aware that though there is some modern art that I enjoy, much of it I find odious, foul and an insult to the term art.

Here's a quotation from that article that I think is very pertinent to 'Modern art':

What Modernists have done has been to aid and abet the destruction of the only universal language by which artists can communicate our humanity to the rest of ...well humanity. It has been a goal of mine for many years to expose the truth of modernist art history, and it is very much on topic to bring into question any practice which purports to analyze art history in a way that deliberately suppresses a valid and correct understanding of what actually happened.

And it is of the utmost importance that the history of what actually took place not be lost for all time due to the transitory prejudice and tastes of a single era. This must be done if art history as a field of scholarship is not to be ultimately discovered to have devolved into nothing more than documents of propaganda; geared towards market enhancement for valuable collections passed down as wealth conserving stores of value.

Successful dealers, who derived great wealth by selling such works...works created in hours instead of weeks... had little trouble lining up articulate masters of our language to build complex jargon presented everywhere as brilliant analysis. These market influenced treatises ensured the financial protection of these collections.

Such "artspeak" as it has come to be known is a form of contrivance which uses self consciously complex and convoluted word combinations (babble) to impress, mesmerize and ultimately to silence the human instinct so that it cannot identify honestly what has been paraded before it.

This is accomplished by brainwashing through authority, confounding the evidence of our senses that otherwise any sane person would question. The "authority" of high positions, and the "authority" of books and print, and the "authority" of certificates of accreditation attached to the names of the chief proponents of modernism, have all conspired to impress and humble those whose common sense would rise up in opposition to what would have been evident nonsense if it had emanated from the mouths and pens of anyone without such a preponderance of "authority" backing them up.

Frederick Ross

Strong words from Frederick, but he's calling it the way he sees it and it's hard to disagree. Sad as it is, in today's art market words have replaced perception. Obfuscation has replaced lucidity and cleverness has replaced craft.

It doesn't have to be that way. I for one refuse to surrender my art to artifice. Every artist should be true to their own inner voice and guidance. The artwork that we leave behind speaks for us more than words ever could. And ultimately the work will speak louder than the 'artspeak' propaganda that supports so much mediocrity these days.

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about 'Hillside' by John Francis Murphy; this was such a fun study to do. I really got a lot out of working at the feet of the Master.

If you tune into today's video narration there is some excellent information provided by David A Cleveland about John Francis Murphy's later period and I highly recommend you check it out.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Painted after - Hillside by John Francis Murphy, Study by M Francis McCarthy - Size 5x7, Oil on wood panel |

This is our last John Francis Murphy today, I saved one of the nicest studies for last. In today's video narration I read from the book A History of American Tonalism 1882-1920 by David A Cleveland, so please check that out.

Yesterday I was reading a very interesting post from a site called artrenewal.org. Artrenewal.org is a site that supports representational art and features the work of many artists throughout history as well as artists, it refers to as Living Masters. They run yearly competitions where they give prizes and they also have a large amount of imagery there. That is always been my predominant attraction to the site.

The article I was reading yesterday was very interesting. It was by a gentleman named Frederick Ross and the title of the article is 'Why Realism?'

I'm providing you with a link to the article here. It is very long and I cannot say that I agree with everything that Frederick says in it, however he makes some excellent points in regards to modern art. Those of you that have read this blog for any length of time will be aware that though there is some modern art that I enjoy, much of it I find odious, foul and an insult to the term art.

Here's a quotation from that article that I think is very pertinent to 'Modern art':

What Modernists have done has been to aid and abet the destruction of the only universal language by which artists can communicate our humanity to the rest of ...well humanity. It has been a goal of mine for many years to expose the truth of modernist art history, and it is very much on topic to bring into question any practice which purports to analyze art history in a way that deliberately suppresses a valid and correct understanding of what actually happened.

And it is of the utmost importance that the history of what actually took place not be lost for all time due to the transitory prejudice and tastes of a single era. This must be done if art history as a field of scholarship is not to be ultimately discovered to have devolved into nothing more than documents of propaganda; geared towards market enhancement for valuable collections passed down as wealth conserving stores of value.

Successful dealers, who derived great wealth by selling such works...works created in hours instead of weeks... had little trouble lining up articulate masters of our language to build complex jargon presented everywhere as brilliant analysis. These market influenced treatises ensured the financial protection of these collections.

Such "artspeak" as it has come to be known is a form of contrivance which uses self consciously complex and convoluted word combinations (babble) to impress, mesmerize and ultimately to silence the human instinct so that it cannot identify honestly what has been paraded before it.

This is accomplished by brainwashing through authority, confounding the evidence of our senses that otherwise any sane person would question. The "authority" of high positions, and the "authority" of books and print, and the "authority" of certificates of accreditation attached to the names of the chief proponents of modernism, have all conspired to impress and humble those whose common sense would rise up in opposition to what would have been evident nonsense if it had emanated from the mouths and pens of anyone without such a preponderance of "authority" backing them up.

Frederick Ross

Strong words from Frederick, but he's calling it the way he sees it and it's hard to disagree. Sad as it is, in today's art market words have replaced perception. Obfuscation has replaced lucidity and cleverness has replaced craft.

It doesn't have to be that way. I for one refuse to surrender my art to artifice. Every artist should be true to their own inner voice and guidance. The artwork that we leave behind speaks for us more than words ever could. And ultimately the work will speak louder than the 'artspeak' propaganda that supports so much mediocrity these days.

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about 'Hillside' by John Francis Murphy; this was such a fun study to do. I really got a lot out of working at the feet of the Master.

If you tune into today's video narration there is some excellent information provided by David A Cleveland about John Francis Murphy's later period and I highly recommend you check it out.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Original painting, Hillside by John Francis Murphy |

Day Ninety Three: November Landscape by Charles Warren Eaton

Hello and welcome to day 93 of 100 days of Tonalism.

Today study is 'November Landscape' by Charles Warren Eaton.

We've done a lot of studies after Eaton in this series. Today study is very representative of his later period, when he was doing a lot of white pines, often silhouetted against sunset or twilight skies. I will be reading some information about Charles Warren Eaton from the book Intimate Landscapes: Charles Warren Eaton by David a Cleveland (which I have just received in the mail), on today's video narration so please check that out.

Today, I'd like to talk about capturing feeling in art. In yesterday's video narration I was speaking about how there are so many feelings that we have, that words cannot describe easily. When you actually think about it, we have a very limited palette with which to render our feelings. We have words like happy, sad, angry or depressed. These words capture only the most extroverted and dense feelings.

For expressing the subtler feelings we have poetry and we have painting. Both of these arts are difficult to master. It is all too easy to make bad paintings and to write bad poetry. For these mediums to appropriately convey the more subtle feelings, the artist or poet must work at their craft for a good while and even then there is no guarantee that they will be able to express anything that actually moves other people.

I was attracted to Tonalism because of the visceral emotive power of this mode of expression. It has taken me many years to get to a point where I feel that I'm doing work that is accurately conveying emotion. When people ask me why I do landscapes and not portraiture or still life, the reason that I give them is that I feel that landscape has the greatest ability to impart emotion, better than any other subject matter. The reason for this is that the landscape is essentially neutral, we all come to it as individuals.

If I were to make a painting of an emotional person it would not have the same ability to move someone especially in the subtle ways that a landscape painting can. If you've ever been outside during a sunset or twilight, you know that special magical feeling that we can all experience. This is a time of enchanting, luminescent light.

Using art to convey emotion is one of the highest accomplishments that any artists can achieve. And by emotion I mean the most profound and ephemeral feelings we have. It's no secret that art can be used to portray the coarser emotions as well, but I see no point in that other than the pursuit of some sort of cleverness.

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about 'November Landscape' by Charles Warren Eaton; I enjoyed doing this study although I felt a bit constrained by the very small size of the panel and, also by the fact that my reference image is a bit blown out.

Like most of Eaton's paintings of white pines so much of the painting's success relies on the contours of the trees against the brighter sky.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Painted after - November Landscape by Charles Warren Eaton, Study by M Francis McCarthy - Size 5x5, Oil on wood panel |

We've done a lot of studies after Eaton in this series. Today study is very representative of his later period, when he was doing a lot of white pines, often silhouetted against sunset or twilight skies. I will be reading some information about Charles Warren Eaton from the book Intimate Landscapes: Charles Warren Eaton by David a Cleveland (which I have just received in the mail), on today's video narration so please check that out.

Today, I'd like to talk about capturing feeling in art. In yesterday's video narration I was speaking about how there are so many feelings that we have, that words cannot describe easily. When you actually think about it, we have a very limited palette with which to render our feelings. We have words like happy, sad, angry or depressed. These words capture only the most extroverted and dense feelings.

For expressing the subtler feelings we have poetry and we have painting. Both of these arts are difficult to master. It is all too easy to make bad paintings and to write bad poetry. For these mediums to appropriately convey the more subtle feelings, the artist or poet must work at their craft for a good while and even then there is no guarantee that they will be able to express anything that actually moves other people.

I was attracted to Tonalism because of the visceral emotive power of this mode of expression. It has taken me many years to get to a point where I feel that I'm doing work that is accurately conveying emotion. When people ask me why I do landscapes and not portraiture or still life, the reason that I give them is that I feel that landscape has the greatest ability to impart emotion, better than any other subject matter. The reason for this is that the landscape is essentially neutral, we all come to it as individuals.

If I were to make a painting of an emotional person it would not have the same ability to move someone especially in the subtle ways that a landscape painting can. If you've ever been outside during a sunset or twilight, you know that special magical feeling that we can all experience. This is a time of enchanting, luminescent light.

Using art to convey emotion is one of the highest accomplishments that any artists can achieve. And by emotion I mean the most profound and ephemeral feelings we have. It's no secret that art can be used to portray the coarser emotions as well, but I see no point in that other than the pursuit of some sort of cleverness.

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about 'November Landscape' by Charles Warren Eaton; I enjoyed doing this study although I felt a bit constrained by the very small size of the panel and, also by the fact that my reference image is a bit blown out.

Like most of Eaton's paintings of white pines so much of the painting's success relies on the contours of the trees against the brighter sky.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Original painting, November Landscape by Charles Warren Eaton |

Day Ninety Two: Moonlight Tarpon Springs by George Inness

Hello and welcome to day 92 of 100 days of Tonalism.

Today study is 'Moonlight Tarpon Springs' by George Inness.

Those of you following this blog will be well aware of the work of George Inness by now. This is our second to last Inness study. One of the major reasons that I undertook this project was in an effort to absorb and integrate more of George Inness' style into my own working methods. I will be reading from the book George Inness by Nikolai Cikovsky on today's video narration, so please check that out.

Today I'd like to talk about working methods and the concept of momentum. I get a lot of people coming in my studio that are either part-time artists or wish to become artists. I'm always stressing with these people that the best way to accomplish that goal is to have a regular working practice and a strong work ethic. You can read all of the books out there, you can take infinite classes and have lots of discussions about it, but there is no substitute for experience when it comes to art.

When I first arrived in New Zealand I was coming off of 26 years of working full time. My first year here in New Zealand I did about 20 paintings. Last year I did around 250. This would include my small studies as well as the larger paintings I've done. I work every day on painting and the only exceptions are days I might go out of town with my wife. I am industrious by nature but I can fall prey to laziness just like everyone else and this is where I think the idea of momentum becomes very important.

By keeping a momentum going in your work life you can avoid many of the deepest lows and yet still accomplish most of the highs. I'm not saying that if you work all the time that you will not occasionally produce a painting that is a dud, that's just how reality works. People are quite surprised when I tell them that landscape painting doesn't necessarily get easier with experience. Your work may improve and you will get better, but painting is so challenging to the spirit and intellect as an occupation, that I can easily see spending another 50 years doing it and still not getting to the bottom of it.

Momentum is one of the greatest allies that you can enlist in this artistic journey. Momentum will keep you moving forward and making progress better than anything else I know. If you stop and start constantly in your artistic life it's a bit like a rocket taking off from the earth. Most of the force and energy required to do it is needed at the beginning. If you're constantly taking large breaks from your work life it means that every time you want to start again you must make a supreme effort. With momentum you are basically coasting on your initial effort and continuing on your journey in a progressive manner.

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about 'Moonlight Tarpon Springs' by George Inness; this painting by Inness has a mysterious quality that I think I painted well.

My drawing is a bit different than George's but I did capture the spirit of his painting in my study and for that reason I am pleased with it.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Painted after - Moonlight Tarpon Springs by George Inness, Study by M Francis McCarthy - Size 5x7, Oil on wood panel |

Those of you following this blog will be well aware of the work of George Inness by now. This is our second to last Inness study. One of the major reasons that I undertook this project was in an effort to absorb and integrate more of George Inness' style into my own working methods. I will be reading from the book George Inness by Nikolai Cikovsky on today's video narration, so please check that out.

Today I'd like to talk about working methods and the concept of momentum. I get a lot of people coming in my studio that are either part-time artists or wish to become artists. I'm always stressing with these people that the best way to accomplish that goal is to have a regular working practice and a strong work ethic. You can read all of the books out there, you can take infinite classes and have lots of discussions about it, but there is no substitute for experience when it comes to art.

When I first arrived in New Zealand I was coming off of 26 years of working full time. My first year here in New Zealand I did about 20 paintings. Last year I did around 250. This would include my small studies as well as the larger paintings I've done. I work every day on painting and the only exceptions are days I might go out of town with my wife. I am industrious by nature but I can fall prey to laziness just like everyone else and this is where I think the idea of momentum becomes very important.

By keeping a momentum going in your work life you can avoid many of the deepest lows and yet still accomplish most of the highs. I'm not saying that if you work all the time that you will not occasionally produce a painting that is a dud, that's just how reality works. People are quite surprised when I tell them that landscape painting doesn't necessarily get easier with experience. Your work may improve and you will get better, but painting is so challenging to the spirit and intellect as an occupation, that I can easily see spending another 50 years doing it and still not getting to the bottom of it.

Momentum is one of the greatest allies that you can enlist in this artistic journey. Momentum will keep you moving forward and making progress better than anything else I know. If you stop and start constantly in your artistic life it's a bit like a rocket taking off from the earth. Most of the force and energy required to do it is needed at the beginning. If you're constantly taking large breaks from your work life it means that every time you want to start again you must make a supreme effort. With momentum you are basically coasting on your initial effort and continuing on your journey in a progressive manner.

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about 'Moonlight Tarpon Springs' by George Inness; this painting by Inness has a mysterious quality that I think I painted well.

My drawing is a bit different than George's but I did capture the spirit of his painting in my study and for that reason I am pleased with it.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Original painting, Moonlight Tarpon Springs by George Inness |

Day Ninety One: Untitled by William King Amsden

Hello and welcome to day 91 of 100 days of Tonalism.

Today study is Untitled by William King Amsden.

William King Amsden is not very well known these days and I've hada bit of a problem finding much biographical information about him on the Internet. I did find one page with some information which I will be reading on today's video narration so please check that out.

In today's blog post I'd like to talk about why I chose to become a Tonalist painter. I knew and I felt that I was going to become a landscape painter in the second half of my life, but I was not aware of Tonalism until about six or seven years ago. After becoming familiar with this artistic movement I knew that I had to find a way to bring what was good and magical about it into my own work as a modern painter.

I was reading a book today called a History of American Tonalism. Those of you that have been following this blog will be very familiar with this book by now as I have been reading sections of it for the video narration of several of the artists that we've covered in this series 100 days of Tonalism.

In his introduction the author David A Cleveland is remarking how it is almost criminal that Tonalism has been forgotten by many Art Historians to a large degree. The roots of modern art are buried within this movement and not in the early part of the 20th century as almost any book on art history will tell you.

I've been known to rant about modern art. The truth of the matter is that I actually like some modern art, though the overwhelming majority of it has no real reason to exist other than to stroke the egos and enrich the bank accounts of artists that have pursued this paper chimera.

The reasons we do art are more important than the substrates we paint on or the materials we use or even the artists that have influenced us. The reason that you paint is the foundation of what you create.

If you are creating work for the good strokes of your fellow artists or validation from the 'art community you essentially have feet of clay and it's hard to believe that the work you create will have any lasting historical significance.

The thing that is powerful about Tonalism and Tonalist paintings is that they are pregnant with emotion and strongly convey what it is to be a human being perceiving nature. This is an innovation that came about after painting movements like the Hudson River school where nature was faithfully copyed in every detail. Those artist strove to objectively depict nature.

While I admire many paintings from the Hudson River school and the Luminists, their work falls flat in comparison to the Tonalist school that came after. The reason for this I think is that Tonalism embraces subjectivity. The landscapes produced by Tonalist painters are brimming with emotion and a sense of being. It is so easy to connect with these paintings that it almost seems like a bit of a conspiracy the way that these artists have been shunted by art history and relegated to the auction houses.

Sometimes that which is moving, subtle and beautiful requires a similar state in the consciousness of the viewer in order to be appreciated. With the advent of modern art, these sorts of ideas have become unpopular and what we are given instead of moving beauty is cleverness disguised as intellectual authenticity.

When I am in nature and I am experiencing the beauty of a sunset or a storm, I am moved very deeply and as an artist I wish to convey that feeling to the best of my ability. This is why when I came across Tonalism I felt like I had found my family artistically.

I do not attempt to make paintings that look old or function as antiques although my work is sometimes perceived that way by people. Instead I endeavor to use the tools that Tonalism has provided to me as a living artist and as a man expressing himself in his own time.

Cheers,

M Francis McCarthy

Landscapepainter.co.nz

A bit about Untitled by William King Amsden; I really like the colors in this painting and the very loose fractured brushwork that William has used.

My reference image was quite lo-res but that is okay, it allowed me more self-expression than many of the other studies in the series. Because the forms are so vaporous and not very well defined it leaves a lot of room for color to convey emotion.

To see more of my work, visit my site here

|

| Painted after - Untitled by William King Amsden, Study by M Francis McCarthy - Size 5x7, Oil on wood panel |

William King Amsden is not very well known these days and I've hada bit of a problem finding much biographical information about him on the Internet. I did find one page with some information which I will be reading on today's video narration so please check that out.

In today's blog post I'd like to talk about why I chose to become a Tonalist painter. I knew and I felt that I was going to become a landscape painter in the second half of my life, but I was not aware of Tonalism until about six or seven years ago. After becoming familiar with this artistic movement I knew that I had to find a way to bring what was good and magical about it into my own work as a modern painter.

I was reading a book today called a History of American Tonalism. Those of you that have been following this blog will be very familiar with this book by now as I have been reading sections of it for the video narration of several of the artists that we've covered in this series 100 days of Tonalism.